Why Won't PostgreSQL Use My Covering Index?

Dear Postgres, Why won’t you use my covering index?

Lately I’ve been learning to tune queries running against PostgreSQL, and it’s …

Read Moreon • 8 min read

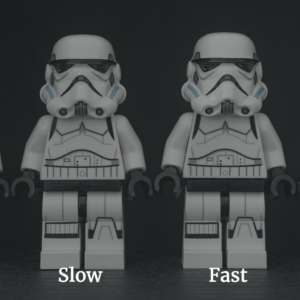

Today’s question is about why a query might be slow at first, then fast the next time you run it.

Watch the 26 minute video or scroll on down and read the written version of the episode instead.

Dear SQL DBA,

Whenever I create a complex view, the first time I use it in a query, the query is slow. The same thing happens after I alter the view. What is the reason behind this?

This is a great question – because when you ask this question, you’re about to discover a lot of interesting, useful things about how SQL Server runs queries.

There are two ways that SQL Server can use memory to make a query faster the second time you run it. Let’s talk about how the magic happens.

SQL doesn’t compile the plan when you create the view– it compiles a plan when you first use the view in a query. After all, you could use the view in a query in different ways: you might select only some columns, you could use different ‘where’ clauses, you could use joins.

Secretly, it doesn’t matter too much that you’re using a view. When you run a query that references it, behind the scenes SQL Server will expand the TSQL in the view just like any other query, and it will look for ways to simplify it.

So SQL Server waits to compiles a plan for the exact query you run.

SQL Server is designed to store the execution plan for a query in memory in the execution plan cache, in case you run it again. It would be very costly for the CPUs to generate a plan for every query, and people tend to re-run many queries.

If you re-run a query and there is already an execution plain in the plan cache, SQL Server can use and save all that compile time.

When you alter a view, this will force SQL Server to generate a new execution plan the first time a query uses the view afterward. Something has changed, so SQL Server can’t use any plans that were in cache before.

Restarting the SQL Server, taking the database offline and online, memory pressure, and many server level settings changes will also clear execution plans out of cache, so you have to wait for a compile.

There are a few ways to see this:

When people use complex views, particularly nested views, they often end up with a LOT of joins in each query.

When SQL Server has a lot of joins, optimization gets harder. There’s a ton of ways the query would be executed.

The SQL Server optimizer doesn’t want you to wait a long time while it looks at every single thing it could possibly do. It takes some shortcuts. It wants to get to a good plan fast.

Generally, SQL Server tries to keep optimization times short, even when you have a lot of joins.

But there are cases where sometimes compilation takes longer than normal.

Usually compilation time is a number of milliseconds, but I have seen some cases where it’s seconds. This could be for a few reasons:

There are more reasons that the second run of a query might be faster.

The first time you run the query it may be using data that is on disk. It will bring that into memory (this memory is called the “buffer pool”). If you run the query again immediately afterward and the data is already in memory, it may be much faster – it depends how much memory it had to go read from disk, and how slow your storage system is.

When you are testing, you can see if your query is reading from disk (physical reads and read ahead reads) by running: SET STATISTICS IO ON;

One difference with this type of memory is that your buffer pool memory is not impacted by ALTERING the view. SQL Server does not dump data from the buffer pool when you change a view or procedure. Instead, it keeps track of how frequently different pages of data are used, and ages out the least useful pages from memory over time.

So this might be part of the answer in your case, but it wouldn’t necessarily explain why the query would be slower on the first run after an ALTER – unless the data pages that you’re using just hadn’t been queried a while and were no longer in the buffer pool cache by chance.

Most queries that reference commonly used tables have a good chance of the data they need being in cache.

To test against a warm cache, I run the query once, and don’t pay a ton of attention to that first run.

I run the query again and measure the duration with the execution plan cached and the data pages in the buffer pool.

If I have a reason to believe that the data won’t be in cache when the query is run, then I will test it against a “cold cache”. I might need to do this if it’s a nightly query that runs, and the data it uses isn’t relevant at all to the daytime workload– so the pages are likely to not be in the buffer pool when it’s time for the job to run that night.

To test against a cold cache, you have to do some things that are NOT friendly for a production server – so make sure you only use this approach against test instances:

Copyright (c) 2025, Catalyze SQL, LLC; all rights reserved. Opinions expressed on this site are solely those of Kendra Little of Catalyze SQL, LLC. Content policy: Short excerpts of blog posts (3 sentences) may be republished, but longer excerpts and artwork cannot be shared without explicit permission.